Where Did Software Go Wrong?

This post has a Portuguese translation, as well as a Russian translation provided by Leonid Popov, who runs pngflare.

Computers were supposed to be “a bicycle for our minds”, machines that operated faster than the speed of thought. And if the computer was a bicycle for the mind, then the plural form of computer, Internet, was a “new home of Mind.” The Internet was a fantastic assemblage of all the world’s knowledge, and it was a bastion of freedom that would make time, space, and geopolitics irrelevant. Ignorance, authoritarianism, and scarcity would be relics of the meatspace past.

Things didn’t quite turn out that way. The magic disappeared and our optimism has since faded. Our websites are slow and insecure; our startups are creepy and unprofitable; our president Tweets hate speech; we don’t trust our social media apps, webcams, or voting machines. And in the era of coronavirus quarantining, we’re realizing just how inadequate the Internet turned out to be as a home of Mind. Where did it all go wrong?

Software is for people

Software is at once a field of study, an industry, a career, a process of production, and a process of consumption—and only then a body of computer code. It is impossible to separate software from the human and historical context that it is situated in. Code is always addressed to someone. As Structure and Interpretation of Computer Programs puts it, “programs must be written for people to read, and only incidentally for machines to execute” (Abelson et al. 1996). We do not write code for our computers, but rather we write it for humans to read and use. And even the purest, most theoretical and impractical computer science research has as its aim to provoke new patterns of thought in human readers and scholars—and these are formulated using the human-constructed tools of mathematics, language, and code.

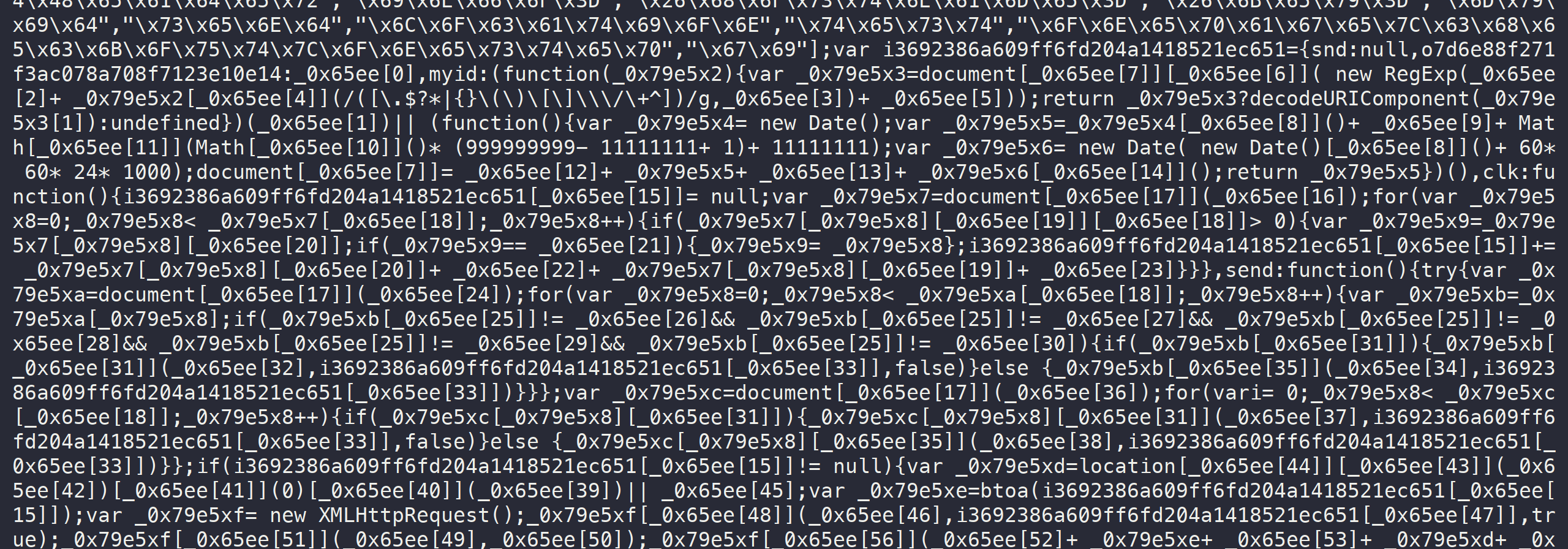

As software engineers, we pride ourselves in writing “readable” or “clean” code, or code that “solves business problems”—synonyms for this property of addressivity that software seems to have. Perhaps the malware author knows this property best. Like any software, malware is addressed to people, and only incidentally for machines to execute. Whether a sample of malware steals money, hijacks social media accounts, or destabilizes governments, it operates in the human domain. The computer does not care about money, social media accounts, or governments; humans do. And when the malware author obfuscates their code, they do so with a human reader in mind. The computer does not care whether the code it executes is obfuscated; it only knows opcodes, clocks, and interrupts, and churns through them faithfully. Therefore, even malware—especially malware—whose code is deliberately made unreadable, is written with the intention of being read.

Code is multivoiced

Soviet philosopher Mikhail Bakhtin wrote that “the single utterance, with all its individuality and creativity, can in no way be regarded as a completely free combination of forms of language … the word in language is half someone else’s” (Wertsch 1991, 58-59). Any code that we write, no matter how experimental or novel, owes a piece of its existence to someone else, and participates as a link in a chain of dialogue, one in reply to another. The malware author is in dialogue with the malware analyst. The software engineer is in dialogue with their teammates. The user of a piece of software is in dialogue with its creator. A web application is in dialogue with the language and framework it is written in, and its structure is mediated by the characteristics of TCP/IP and HTTP. And in the physical act of writing code, we are in dialogue with our computer and development environment.

Wertsch formulated Bakhtin’s notion of dialogues in terms of voices: “Who is doing the talking?,” he asks—“At least two voices” (1991, 63). While Wertsch and Bakhtin were concerned with human language, we can just as readily apply their insights to software: “the ambiguity of human language is present in code, which never fully escapes its status as human writing, even when machine-generated. We bring to code our excesses of language, and an ambiguity of semantics, as discerned by the human reader” (Temkin 2017). Whose voices do we hear when we experience code?

At the syntactic level, every keyword and language feature we use is rented from the creators of the language. These keywords and grammars are themselves often rented from a human language like English, and these voices too are present in our code. The JavaScript if rents meaning from the English “if,” which is itself rented from German, and in any case, the word does not belong to us, not fully—the word in language is half someone else’s. When we call programming languages, libraries, and frameworks “opinionated” or “pits of despair/success,” we really mean “how loud is the voice of the language in our code?” A comment on the Go programming language by matt_wulfeck on Hacker News illuminates the intentional imbalance between the voice of the programmer and the voice of the language:

Go takes away so much “individuality” of code. On most teams I’ve been on with Python and Java I can open up a file and immediate tell who wrote the library based on various style and other such. It’s a lot harder with Go and that’s a very good thing.

Here we see how voices mediate our action—how does Go mediate the way we write and think about code? Jussi Pakkanen, creator of the Meson build system, called the mediating aspect of voices shepherding: “It’s not what programming languages do, it’s what they shepherd you to.” Shepherding is “an invisible property of a programming language and its ecosystem that drives people into solving problems in ways that are natural for the programming language itself rather than ways that are considered ‘better’ in some sense” (Pakkanen 2020). We internalize the voices of our social relations, and these voices mediate our action. Every time we dive into a codebase, speak with a mentor, take a course, or watch a conference talk, we are deliberately adding new voices to the little bag of voices in our mind. This is not purely a process of consumption: in internalizing voices, we form counter-words, mentally argue with them, and ventriloquize them through our own work—in a word, we engage in a dialogue.

Next time you settle down to read some code, listen carefully for the voices inside the code and the voices inside your mind, however faint they sound. I can hear the voice of a senior engineer from my last job every time I write a type definition.

Abstraction and labor

At a higher level, the patterns and strategies we use to structure our code, which we think of as independent of programming languages, such as algorithms, design patterns, architectures, and paradigms, are rented too. Some algorithms are named after famous computer scientists like Dijkstra, Kruskal, and Prim, and these clue us into the rich ensemble of voices speaking in our code. But at the same time, the process of naming obscures the multitude of other voices speaking through these algorithms. Dijkstra’s algorithm is a weighted breadth-first search that uses a priority queue—but the name alone would not tell you this, and in fact, the names “breadth-first search” and “priority queue” obscure still more voices. By attributing the entire history, the chains of dialogue, and the chorus of voices that speak in the algorithm, all to that single name Dijkstra—by seeing one where there are many—they are killed, and the signifier Dijkstra takes their place. This is the process of abstraction.

These obscured chains of dialogue are present in everything, from supply chains, to APIs, source code, and package managers. Run git log in a repository from work, or browse the commits of an open source project—try Postgres if you don’t have one handy. Read the commit messages, puzzle over the diffs, and marvel at the layers of sedimented history. Postgres has nearly 50,000 commits, one in reply to another, each representing hours or days of labor, and lifetimes of accumulated knowledge and experience. It is a recording surface for these dialogues, in which each commit is inscribed; and it is at the level of commits, changelists, and releases that we tame the continuous flow of development by cutting into, segmenting, and abstracting it into units that we can comprehend. One voice at a time, please. One spokesman Dijkstra, one mascot Postgres to hide the complexity.

Every piece of software that we interact with, every company, every project, every product—from your computer’s operating system, to the SaaS vendors your company relies on, the libraries you use, and the routines running on the microcontroller in your refrigerator, hides just as delightfully complicated of a history of production, and this is what brings all of software development together. Marx described this common substance “a mere congelation of homogeneous human labour, of labour power expended without regard to the mode of its expenditure. All that these things now tell us is, that human labour power has been expended in their production, that human labour is embodied in them. When looked at as crystals of this social substance, common to them all, they are—Values” (1867, 48).

NPM is not the problem

In 2016, a JavaScript package called left-pad broke the Internet for a day. The package consisted of eleven lines of code that padded strings to a specified length, turning strings like “5” into strings like “005.” Out of protest over a trademark dispute, left-pad’s creator Azer Koçulu deleted it from the NPM registry, wreaking havoc on an entire ecosystem of packages that depended on it, whether directly or indirectly through transitive dependencies to the nth degree—and these were packages that powered thousands of websites around the world (Williams 2016).

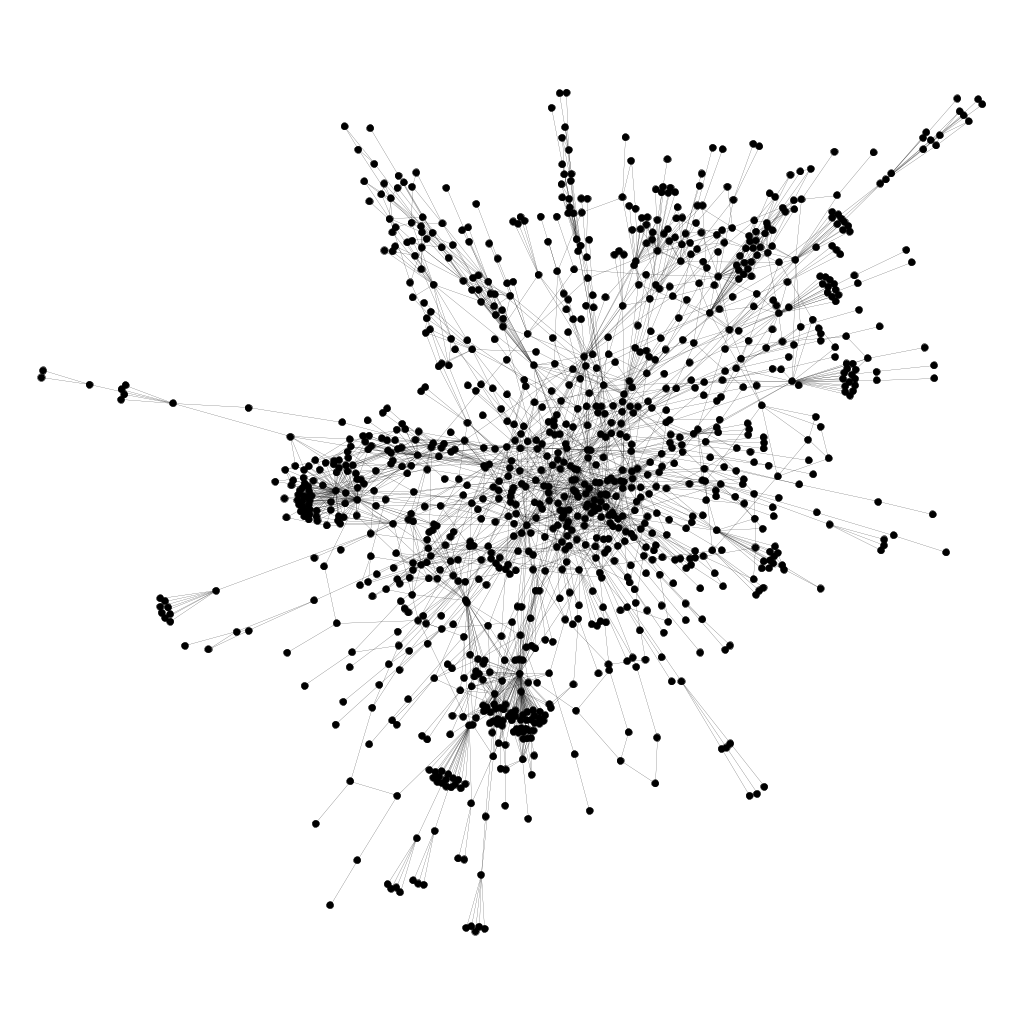

A visualization of the dependency graph for the react-scripts NPM package. Each dot represents a package, and lines connect packages that depend on one another. One of the dots is left-pad; I don’t know which.

According to the discourse at the time, this was a lesson on the fragility of the webs of dependencies and abstractions that we had created, and it was a sign that the NPM ecosystem was fundamentally broken. We had built houses of cards—long chains of dialogue whose links could simply vanish—and all it took was a single developer and his eleven lines of code to tear them down. David Haney, meditating on the left-pad incident, asked in a blog post

Have We Forgotten How To Program? […] I get the impression that the NPM ecosystem participants have created a penchant for micro-packages. Rather than write any functions or code, it seems that they prefer to depend on something that someone else has written

(2016).

But we know by now that we have not forgotten how to program: this is how we have always programmed. Everything we write is something that someone else has written; nothing belongs to us; all code is multi-voiced. These webs of dependencies have always existed, but perhaps no system had made the fact quite so obvious as NPM did. Where we see one—one app, one script, one package—the breakages of NPM remind us that there are many.

Software is not creative

Watch as a neural network, initialized from random chaos, trains itself to play Atari Breakout. Watch the tiny machines—the nodes of the network, their connections and conjunctions, break-flows and back-propagations—and watch them converge: at first random contingencies that, in a feedback loop, crystallize into structure. These are machines reproducing machines. These are tiny capitalists. “Universal history is the history of contingencies, and not the history of necessity. Ruptures and limits, and not continuity” (Deleuze & Guattari 1983, 140).

But neural networks, and software in general, do not create new reality—they ingest data and reflect back a reality that is a regurgitation and reconfiguration of what they have already consumed. And this reality that these machines reflect back is slightly wrong. Recall the statistician’s aphorism “all models are wrong, but some are useful.” What happens when we rely on these models to produce new realities, and feed those slightly-wrong realities back into the machines again? What happens when we listen to Spotify’s Discover Weekly playlist week after week, “like” the posts that Facebook recommends to us, and scroll through TikTok after TikTok? I am guilty of all of these, and it would not be wrong to claim that my taste in music and sense of humor are mediated by this mutual recursion between the algorithms and the real world.

And that is exactly it: in the modern world, our social interactions, our devices, governments, and markets, are circulations and flows of the same realities under the same rules. Our software creates new problems—problems that we’ve never had before, like fake news, cyberbullying, and security vulnerabilities—and we patch them over with yet more layers of code. Software becomes quasi-cause of software. These are echoes of the same voices in a positive feedback loop, growing louder and less coherent with each cycle—garbage in, garbage out, a thousand times over.

Who does software benefit?

For many of us fortunate enough to stay home during the coronavirus outbreak, our only interface with the world outside our families and homes—the relays of connection between us, our families, communities and societies—have been filtered through our screens and earbuds. It is apparent now more than ever exactly what software does for us, and what kinds of inequalities it reinforces.

Through Instacart, Amazon Fresh, and other grocery delivery services, we can use an app to purchase a delivery driver’s body for an hour to expose themself to the virus on our behalf. Unsatisfied with even this, some developers have written scripts to instantly reserve the scarce delivery slots on these services.

One developer wrote to Vice’s Motherboard “I designed the bot for those who find it extremely inconvenient in these times to step out, or find it not safe for themselves to be outside. It is my contribution to help flatten the curve, I really hope this’ll help reduce the number of people going out” (Cox 2020). Is that right? Does a bot really reduce the number of people going out, or does it merely change the demographics of who gets to stay home, favoring those with the resources and technical skills to run a Python script and Selenium WebDriver? With a constant and limited number of delivery slots, Joseph Cox points out that these bots create “a tech divide between those who can use a bot to order their food and those who just have to keep trying during the pandemic” (2020).

Instacart bots are just the most recent reincarnation of a long tradition of using the speed of software to gain an edge against humans. In the 2000’s, when concert tickets first started to sell over the Internet, scalpers built bots to automatically purchase tickets to resell them at a higher price. And capitalism, in its infinite flexibility, adapted and welcomed this development with open arms and invisible hands, spawning companies like TicketMaster, which institutionalized and legitimized the practice. But Instacart and TicketMaster are mere symptoms of the problem. We saw the same patterns in the arms race of high-frequency trading. At first, the robots beat the humans. Next, the robots became part of the game, and the robots played against each other. The profits from high-frequency trading dried up, and yet using it became a necessity just to keep up.

These examples give us a decent idea of what software is good for. On its own, it never enables anything truly new, but rather changes the constant factors of speed and marginal cost, and raises the barrier for participation arbitrarily high. Once the software train begins to leave the station, we have no choice but to jump and hang on, lest we get run over or left behind—and we are not sure which is worse. Max Weber, studying the development of capitalism, identified this secularizing, spiralling effect:

The Puritan wanted to be a person with a vocational calling; we must be. For to the extent that asceticism moved out of the monastic cell and was carried over into the life of work in a vocational calling, and then commenced to rule over this-worldly morality, it helped to do its part to build the mighty cosmos of the modern economic order. This economy is bound to the technical and economic conditions of mechanized, machine-based production.

(Weber 1920, 177)

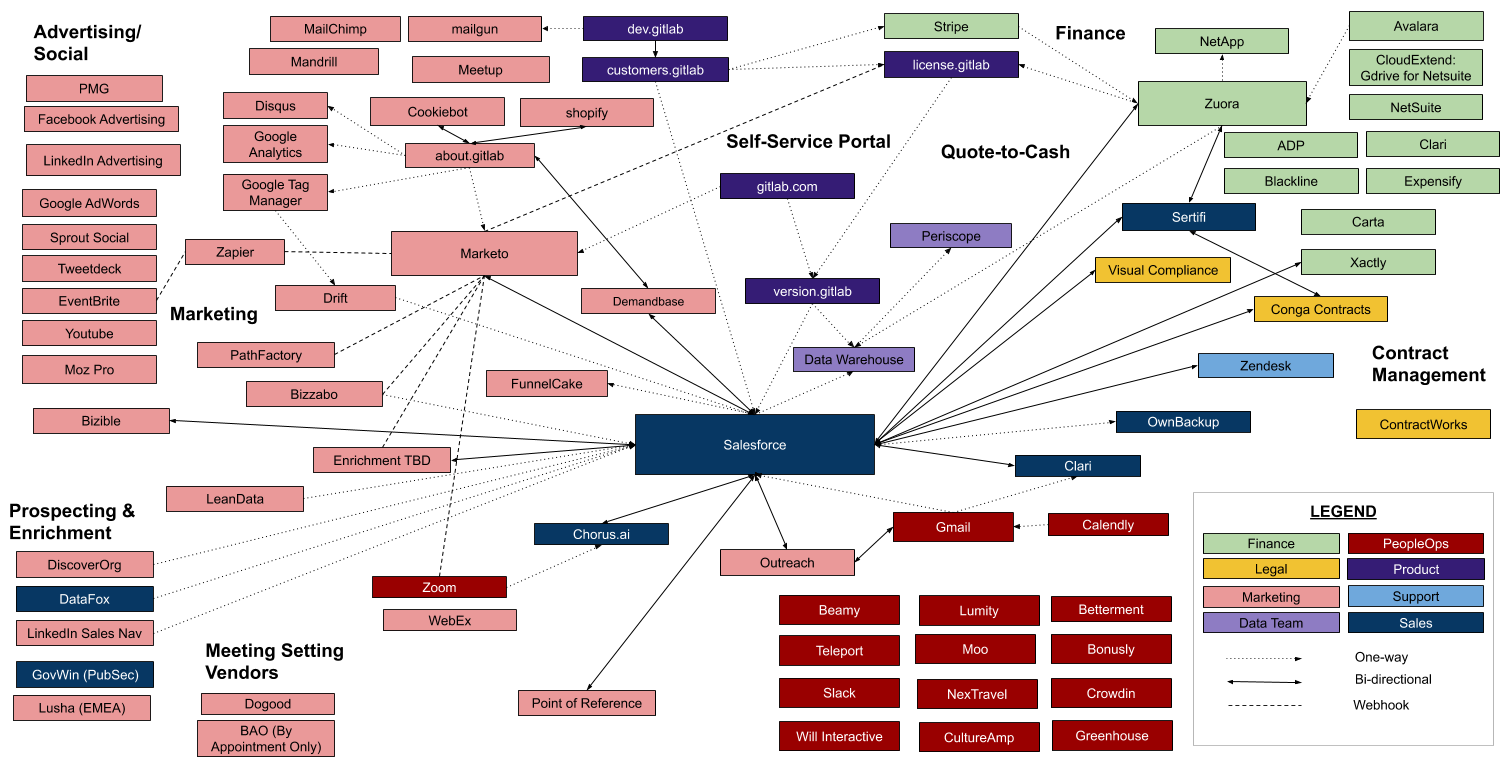

A false start: startups

Startups love to save the world, but look at the state of the world now—is this what it’s like to be saved? Is the world even a little bit better because of startups like Instagram, Uber, and Peloton? Startups are spaces of remarkable innovation, and they are experts at channeling the multivoicedness of code—just look at the network of voices that GitLab channels (visualized below). But under capitalism, these voices are distorted and constrained, and they cry “growth, growth!” as venture capitalists and founders demand user acquisition, market share, and revenue—in a word, they demand access to capitalist accumulation.

Systems diagram published by GitLab

The startup founder, no matter how much they claim to love code, love humanity, or love the thrill of the hustle (and they may even believe themself when they say it), loves the growth of capital most of all. The tech founder is a capitalist proper, but capital does not love them back; capital cannot love at all, and the odds are stacked against our hero capitalist. “The larger capitals beat the smaller … It always ends in the ruin of many small capitalists, whose capitals partly pass into the hands of their conquerors, partly vanish” (Marx 1867, 621). Capital accumulates and concentrates, and in the midst of frothy competition, the startup either dies or gets acquired by Facebook or Google, leaving nothing behind but a bullet point on LinkedIn and a blog post signifying an incredible journey. So much for changing the world.

What is to be done?

To revisit that ambitious question we set out to answer, where did it all go wrong? What got us into this mess, this tool-assisted speedrun of accumulation and exploitation? The trick is that we have not been studying software on its own—we’ve established that computers and computer code are veritably saturated with human touch, human voices, and human thought. Software cannot be divorced from the human structures that create it, and for us, that structure is capitalism. To quote Godfrey Reggio, director of Koyaanisqatsi (1982), “it’s not the effect of, it’s that everything exists within. It’s not that we use technology, we live technology. Technology has become as ubiquitous as the air we breathe, so we are no longer conscious of its presence” (Essence of Life 2002).

Where did it all go wrong? At some point, capital became the answer to every question—what to produce, how to produce, for whom to produce, and why. When software, that ultimate solution in search of a problem, found the questions answered only by capital, we lost our way, caught in capital’s snare.

Q: What does software do?

A: It produces and reproduces capital.

Q: Who does software benefit?

A: People who own capital.

Q: What is software?

A: Capital.

A: Capital.

A: Capital.

A: Capital.

But we can break this pattern; we can find our own answers to those questions, and if it’s up to us, the answer does not need to be that answer we’ve been taught, capital. Software is a tool with revolutionary potential, but that is the extent of what it can give us. “Science demonstrates by its very method that the means that it constantly elaborates do no more than reproduce, on the outside, an interplay of forces by themselves without aim or end whose combinations obtain such and such a result” (Deleuze & Guattari 1983, 368).

So, what are the aims and ends that we should direct our software toward? What are the answers to those economic questions, if not capital—or better yet, what questions should we be asking, if not economic?

I don’t know :)

Consider donating to a local community bail fund.

Protesters across the nation are directly fighting the oppressive structures outlined in this post. Your money will pay for legal aid and bail for people who have been arrested for standing up to police brutality, institutional racism, and the murder of Black men and women like George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, and Nina Pop.

At the moment, this is the most efficient means of converting your capital into freedom. If software is good for anything, this is it.

https://www.communityjusticeexchange.org/nbfn-directory

References

Abelson, Harold, Gerald Jay. Sussman, and Julie Sussman. Structure and Interpretation of Computer Programs. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1996.

Cox, Joseph. “People Are Making Bots to Snatch Whole Foods Delivery Order Time Slots.” Vice. Vice Media Group, April 21, 2020. https://www.vice.com/en_us/article/n7jaw7/amazon-fresh-whole-foods-delivery-time-slot-bots.

Deleuze, Gilles, and Félix Guattari. Anti-Oedipus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. Translated by Mark Seem, Robert Hurley, and Helen R. Lane, 1983.

Essence of Life. MGM Home Entertainment Inc., 2002. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8oiK4vPLtVw&t=581.

Haney, David. “NPM & Left-Pad: Have We Forgotten How To Program?” David Haney, March 23, 2016. https://www.davidhaney.io/npm-left-pad-have-we-forgotten-how-to-program/.

Marx, Karl. Capital: a Critique of Political Economy. Translated by Ben Fowkes, 1867.

Pakkanen, Jussi. “It’s Not What Programming Languages Do, It’s What They Shepherd You To.” Nibble Stew, March 6, 2020. https://nibblestew.blogspot.com/2020/03/its-not-what-programming-languages-do.html.

Temkin, Daniel. “Sentences on Code Art.” esoteric.codes, December 27, 2017. https://esoteric.codes/blog/sentences-on-code-art.

Weber, Max. The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism. Translated by Stephen Kalberg, 1920.

Wertsch, James V. Voices of the Mind: A Sociocultural Approach to Mediated Action. Cambridge University Press, 1991.

Williams, Chris. “How One Developer Just Broke Node, Babel and Thousands of Projects in 11 Lines of JavaScript.” The Register. Situation Publishing, March 23, 2016. https://www.theregister.co.uk/2016/03/23/npm_left_pad_chaos/.